|

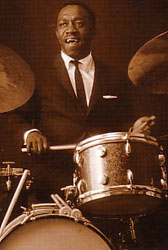

(and them Jazz Messengers)

One of jazz’s MVP drummers, Blakey has a seemingly endless resume, and as the leader of the perpetually changing Jazz Messengers, he fostered generations of new players, many of whom went on to lead their own groups. It was the school of real knocks, the boot camp from which one emerged a stronger individual. As much as Blakey’s aggressive drumming style is immortal, his nurturing of jazz’s future stands equal in importance. I almost got to see him in concert once, but he fell ill and canceled, and he died not long after. A Night at Birdland, Vols. 1 and 2 Feb. 21, 1954 / Blue Note RVG “First record session I ever enjoyed,” Art Blakey says to the crowd at one point, and there’s much sense in setting up microphones at a live gig to make a quality record (or two). As it happens on this Birdland date, Clifford Brown (trumpet), Lou Donaldson (alto sax), Horace Silver (piano), Curly Russell (bass), and the ever-swinging Blakey throw down the gauntlet and burn brightly without inhibition or end. While there’s no mystery, ambiguity, or romance here, the way this group relentlessly pushes through every tune (even the ballads, really) and makes it all sound so effortless and friendly is something to admire. More craft than art, but high craft it is. Volume 1 might be the dominant twin due the marvelous “Split Kick”, Brown’s ballad feature “Once In A While”, and a couple of smoking numbers in “Quicksilver” and “Mayreh”. “A Night In Tunisia” doesn’t have the episodic formality of the 1960 studio take but is dramatic nonetheless, partly from the way Brown and Silver begin their solos. Bonus tracks on the Volume 1 CD include the complex “Wee-Dot” blues and another improvised 12-bar jam. Volume 2 doesn’t slouch far behind, containing Lou Donaldson’s spotlight “If I Had You”, a couple of Birdsongs in “Now’s the Time” and “Confirmation”, further explorations of “Wee-Dot” and “Quicksilver”, and a bonus “The Way You Look Tonight”. Both volumes could have been united in a two-disc reissue without any aesthetic problem, but I suppose Blue Note wanted to retain the color-coded integrity of the separate original releases. The upgraded sound is pretty good, considering the imperfect source; the remaster adds some clarity and enhances valuable bass frequencies. (And I’d like to thank a buddy for providing me with a cassette compilation of this gig years before I finally got the remastered discs.)

When thinking of these recordings, my main impression has always been of the amazing abilities of Clifford Brown. Between this and his work with Max Roach, Clifford was one of the brightest stars of the hardbop era. Beyond that robust trumpet tone and fluid technique is a style so melodic you could make a tune out of almost any four bars of his solos. Lou Donaldson blows up a similarly soulful storm while the rhythm trio lays it down tight and true. This is very busy music and a little goes a long way with me, but it’s undeniably strong. Lastly, put your hands together for Birdland emcee Pee Wee Marquette - Thank ya!

They meshed from day one with Monk’s Blue Notes, and subsequent Monk recordings with Blakey never lacked spark. You might even say that Monk’s instructions to his later drummers (“Just swing, then swing harder”) were built on the Blakey experience. For his part, Blakey always took delight in the pianist’s tunes. So why not have Monk sit in with the Messengers, who at this time included Bill Hardman, Johnny Griffin (soon to be a Monk sideman himself), and Spanky DeBrest. Except for Griffin’s blues “Purple Shades”, the material all comes from Thelonious. On the surface, it’s good fun - end of general recommendation. Yet listen closer and there’s a weird incongruity between Griffin’s exuberance, Hardman’s wannabe exuberance (his ideas seem to run to the very edge of his technique), and Monk’s sense of space. By space, I mean having the pianist take so long between phrases that you might think you’re listening to a bass solo. (Although this isn’t the first or last instance where Monk puts the listener in that position!) For example, “Evidence” rockets out of the gate with Hardman and Griffin in hot form, while the tense pauses in Monk’s solo make quite a contrast. Same goes for the hesitant piano statement in “In Walked Bud”. Monk is at his most entertaining on “I Mean You”, where he begins with the final trill of Griffin’s preceding solo, and then grabs Art in some call and response before devising other ideas. But most of his solos are reticent. Not so his accompaniment, which by the time of “Rhythm-a-ning” becomes rather devilish. None of this throws Blakey, whose inspired percussion peppers every tune.

The deluxe edition’s alternate takes tell more of the story. The alternate of “Evidence” must have been an early take, as Hardman drops some clams into the melody statements, but Monk’s solo is more energetic than on the master, or indeed anything on the regular LP program. On the issued (later?) take, Hardman nails the melody, while Monk has apparently withdrawn, unwilling to repeat his ornate solo from the earlier take. Or so I hear it. The alternate “Blue Monk” also has a touch more pep from the piano as well. In any case, these are sideline nuances in an idiosyncratic and ultimately good session. It’s a 1950s Atlantic recording, so beware the thin sound, even in the remastered version.

Introducing the new-look Messengers: Lee Morgan (trumpet), Wayne Shorter (tenor), Bobby Timmons (piano), and Jymie Merritt (bass), with Mr. Blakey on stick patrol. Four-fifths of the lineup had already cut the album Africaine, which went unreleased at the time, so The Big Beat was the new band’s wax premiere. It takes cues from the past but envisions a more complex future. Wayne Shorter contributes the modern elements in his solos and writing. “Sakeena’s Vision” is totally in line with the post-bop sound that would dominate the decade. Suggestive as the chord changes might be, it’s not enough to deter Art from tossing in a typically primal drum solo. Wayne probably tailored “The Chess Players” to look back to the more soulful Jazz Messenger sound, and his solo has some good bait in it. “Lester Left Town” was already cut during the Africaine sessions, and according to these new liner notes, it apparently made producer Alfred Lion balk at the time. That’s strange, because Lion had recorded far more advanced music, and “Lester Left Town” turns out to be the catchiest track on this album. Set at a snazzy tempo, it has a descending line as its main hook with a chordal trip in the bridge. Maybe Lion wanted Blakey to deliver more of the simplicity of the Silver or Golson days, but in the end, “Lester Left Town” remains a classic.

The three other tracks are solid, too. “Politely” is a blues that writes itself, and I hear the chromatic movement in the beginning of Wayne’s solo as a sarcastic take on bop’s passing lines. Timmons’ “Dat Dere” is a dark sequel to his groovy hit “This Here”. It’s at a jukebox tempo that Blakey occasionally turns into a march, and it has enough chord movement to be more than just a mindless soul-jazz piece. In the riveting rearrangement of “It’s Only a Paper Moon”, Merritt walks during the theme, while drums, tenor, and piano toll a low note every eight beats, giving the vamp a sort of Native American feel. Above this, Morgan paraphrases the melody with a lightly daubed tone. The body of the tune falls into standard rhythms, and the vamp returns at the fading end. An alternate take follows. Not an essential record overall, but full of strong improv and a couple of fine compositions.

With Morgan, Shorter, Timmons, and Merritt. The title tune takes a wild eleven-minute ride that includes a pounding percussion section, hot solos, and a false ending or two. No Jazz Messengers collection could be complete without it, and despite Blakey’s liner note claim that they played it differently every night, the ensemble parts sound entrenched. It isn’t the definitive reading of Dizzy’s popular tune (which actually gets lost in the hoopla), but it’s surely the most theatrical. Elsewhere, Shorter’s compositional richness continues with “Sincerely Diana”, and Morgan contributes the wonderful, laid-back “Yama”. Timmons provides the expected boogie groove with “So Tired”, which takes a challenging detour in its mid-section. The bonus track “When Your Lover Has Gone” has none of the pathos you might hear from a Rollins version, as Art’s stickwork suggests something breezier.

Shorter’s brilliance as a writer is in finding new ways to exploit tension and resolution. He does it in different locations, with different bar lengths and intriguing melodies. His themes are usually as interesting as the solos they produce, and “Sincerely Diana” is a great one. I think it’s the best track on the album, even though “A Night in Tunisia” hogs general attention.

More from the Tunisia studio session, released a few years later. Instead of the common image of Blakey’s scrunched-up ciggie-puffing mug on the cover, it’s a smiling couple who look like they’ve just exchanged their first I-love-you’s. However, the Jazz Messengers haven’t gone soft - this is a swinging collection in their usual suit. The lengthy title track opens with a slightly romantic air and then marches underneath long solos by Morgan and Timmons. Interestingly, Wayne sits this one out, except for some backing notes in the ensembles. The following “Johnnie’s Blue” typifies the Jazz Messenger approach to blues-bop and has a great bassline to boot. Three other tunes come from Shorter, and the two uptempo ones (“Noise in the Attic” and “Giantis”) are very catchy. “Noise in the Attic” also contains one of Wayne’s strongest recorded solos from any era - listen to him proclaim the whole thing. In the lovely waltz “Sleeping Dancer Sleep On”, Blakey appropriately keeps his men at a low dynamic; the alternate take is fine, except for a few wayward notes. In the end, both this and the Tunisia album are well worth owning.

Fun hardbop from a great sextet. Freddie Hubbard, Wayne Shorter, and Curtis Fuller do the lung work, and Cedar Walton and Jymie Merritt stoke the rhythm fires with the leader. This is the most rewarding Messengers lineup in my estimation, as they venture into sophisticated areas while keeping a down-home vibe. Shorter’s “Contemplation” is a close relative to Coltrane’s “Naima” in the long tones and light bass pulses, though the group scoots into double-time almost out of reputation. “Reincarnation Blues” is another treat from Wayne that finds the horns behaving in canon-like fashion. Best of all is the title track written by Fuller, one of the cheeriest hardbop tunes ever. This is especially brought to light in the improvisations, where one hears a happy five-note counterline and bright accompaniment from Walton, topped by a drum solo full of tension and space. The arrangement of “Moon River” is just bizarre, though, as it transforms the dainty melody into an uptempo fanfare of big band power. Good alternates grace the RVG issue. This would be my favorite Blakey disc if it weren’t for the stiff competition of Free for All; grab it soon if you don’t have it already.

An intense, hardcore record. Hard to overstate the impact of the title track, in which the soloists alternate between dark and light modes and pilot the Messenger ship into uncharted space. Shorter takes a ferocious solo, and as he is the composer, he sews the modal joins with surety. Neither Fuller nor Hubbard, who both play well, can match Wayne’s statement. The tenor is also responsible for “Hammerhead”, a masculine bopper sleek as its namesake. Freddie’s “Core” begins with a Trane-ish bassline from Reggie Workman and nearly hits the intensity level of the title track. Blakey revels in the new territory, exhorting his sidemen to push, push, push. “Pensativa”, in a Hubbard arrangement, moves to a spiky Latin beat and takes the album out with style. Not much else to say, as the music speaks loud enough for itself.

Returning trumpet man Lee Morgan sounds just a wee bit tinny and strained in places. On the other hand, his licks are more incisive than Hubbard’s - six of one, half dozen of the other. Coltrane continues to be an influence in the semi-dark modal vamp of Fuller’s “The Egyptian” and in the way Shorter plays “When Love Is New”, a nice Cedar Walton ballad. Shorter’s “Mr. Jin” sounds a lot like the music that would appear on his Speak No Evil album, and the bonus cut “It’s a Long Way Down” isn’t far off that mark either. Traditional bases are covered by “Sortie” and “Calling Miss Khadija”, and the latter’s got a hip groove to introduce its blues changes. The drums blast through on almost every cut. On “The Egyptian” (the best track, by the way), the piano and bass could have come from any contemporary Coltrane recording, and Blakey thus shows how he might have sounded underneath said giant. The trills underneath Fuller’s solo certainly recall “Africa”, don’t they? File the record under Indestructible, despite the fact that the lineup would be deconstructing soon. Highest marks go to Walton and Blakey for their performances.

|