|

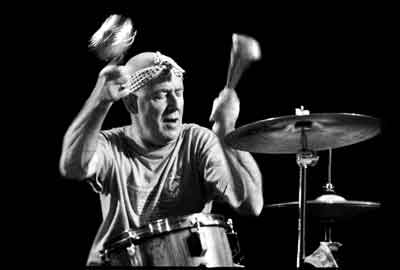

“He’s a real Nietzschean at the traps: believes whatever doesn’t kill the people he plays with will make them stronger. If he really likes you, he may try to mow you into the ground: force you to come up with something in the breach. It works, too. He is also more responsive to his immediate environment that just about any musician you can name, eye always out for some backstage detritus that can be used as an on-stage prop.” - Kevin Whitehead, liner notes to a Clusone Trio album The above is hard to follow as a nutshell description of drummer Bennink, except to reinforce the sense of aliveness. Some might balk at his humor - the physical acrobatics, the visual and aural sideshows - but this is an extension of his joie de vivre in playing. It’s not necessarily an adaptation of the extracurricular “entertainer” role. But nevermind the clogs, the pushbroom on the stage floor, the newspaper fire in the hi-hat; give him two brushes and a snare and he’ll swing the pants off anyone in earshot. Han is one of a kind.

Bennink has been a mercenary sideman for decades, and his full discography is huge, a lot of it duets with brave souls. Below are some solo and collaborative titles.

A wild free improv vortex with outland tenor Peter Brotzmann, pianist Fred Van Hove, and Bennink on drums and miscellanea. Rather than take responsibility for a Brotzmann review page - and unwittingly steer nice people to sonic horror - I’m grouping this with Han’s records, and his percussive assault leads the music in any case. (He also blows his gachi instrument, which I guess makes the trombone and didgeridoo sounds.) The six tracks are roughhouse melees occasionally guided by Van Hove’s piano, and taken to mad extremes by Brotzmann’s overblown phrases. There are spaces between the storms, along with peaceful moments from Bennink (the steel drums and woodblock mosaics) and a few “happy” piano parts. The battlefield being what it is, though, nothing stays in place for long, and Brotzmann is pretty annoying - I don’t think even fans of his mangled, abrasive sax would rate these disruptions as prime Peter. Meanwhile, Bennink and Van Hove share a peculiar chemistry, and that’s the only enjoyment I ever really got out of this record.

Now this one is downright fun while being quite the free-for-all. Ten short tracks concentrate the trio in an energetic, abstract, humorous mash. Peter Brotzmann explores alto, bass, and baritone sax in addition to his usual lacerating tenor, and he’s in good form. Fred Van Hove plays both piano and celesta; some of his casual phrases sound so delightfully odd amidst this din. Han Bennink pummels all sorts of percussives (junk or proper), along with howling through wind axes or toying with a primitive rhythm box (or tape machine?). When no instruments will do, Han vocalizes: overtone chanting meets Tazmanian Devil. The trio covers a lot of ground in their improvisations - gentle piano/celesta, startling drum ambushes, staccato bass sax signals, boogie-woogie riffs, insane vocalizing, and the inevitable wallpaper-peeling frenzies. Midway though the record emerges the otherworldly soundscape “Gere Bij”, where breathy sax and wavering melodica (or accordion? or who knows what?) create a poignant atmosphere. It’s nice that Brotzmann accesses more of the saxophone family because you never know what’s next from him, like a blitzing soliloquy or sensitive support drones. You never know when Van Hove will revert to saloon-style piano or make a classical reference or blast the keyboard to pieces. And you have no idea what crazy tangent Bennink has up his sleeve. His ear for the dramatic - and the absurd - is invigorating.

Despite its segmental nature, the program almost has a thematic flow as certain configurations reappear out of nowhere. The only bad moment is the squealing eardrum buster “Concerto for 2 Clarinets”. This album was originally a Free Music Production and was reissued (with great sound) as an Archive FMP Edition on Atavistic.

A live solo performance with Bennink tackling more than just drums. There’s a clarinet (?) solo over a drum machine, some trombone-ish blatting, a berimbau (I think), and a growling didgeridoo-like contraption. The four-minute snare crescendo “Bumble Rumble” serves as induction rite, and from there, two long tracks feature Bennink moving from one axe to another. The horn solos are more about energy than notes; it’s a natural urge for Han to make noise, and anything will do, as long as he gets to expend effort. The audience is generous with attention, and one can hear from the stereo movement that Han is to and fro on stage. He occasionally engages the crowd with applause cues, dramatic silences, and humor - the show ends with a violent scream followed by the harmless ting of a bell.

The trapset solo on “Spooky Drums” turns fluttering woods and skins into a metallic assault (cymbal wash, snare frenzy) with possessed vocals amidst the din. Han vocalizes a few times across the album, perhaps as a signal to the audience or as inspiration to himself? “Yowwww!!” - WHAP. Beyond the usual drums are tablas, woodblocks, rattles, bells, buzzing membranes, metals, tubes, etcetera, all subject to abuse. When the trip between stations is too long, he’s happy to kneel on the floor and play that, too. Bennink’s drumming is better heard on plenty of other group albums, but this solo trip is an amusing one.

Pianist Melford holds her own against Han in this largely improvised duo date. The blues and older songs are referenced at regular intervals, like the sultry “How Long Blues”, the old-timey ditty “Some Relief”, and a deconstructed “Maple Leaf Rag”. These tracks serve as good-humored oasis points between the abstract pieces. “The First Mess” indicates how things will go: Melford plays soft, ominous notes as Han rudely punctuates. Freakouts like “Now” and the title track balance Melford’s chord fragments against flail tank drumming. Melford’s classical precision only gives way to hammering abandon when it’s clear that Bennink will take the blame if any bystanders get hurt. The nine-minute highlight “Which Way is That?” starts with a thrust and parry game and then constructs a chord vamp and melody lines over a four-on-the-floor groove. Another gem is “And Now Some Blues”, splattering boogie-woogie across a minefield of tension and release. The two players listen closely to each other, even in the anarchic moments, and proof is heard whenever they slam a climactic phrase together.

As fine as Melford’s piano playing is, Bennink dominates. His well-recorded percussives include a trapset, a bell that he proudly rings on occasion, and a few unidentifiable objects. The solo piece “Another Mess” is a guessing game of sounds: a cymbal is dropped and vibrates to a stop on the floor, metal objects are clicked, and a strange membrane hums. It’s as if Han was turned loose in a garage. “To whom am I expressing myself?” he wonders aloud before paradiddling the next shelf. This album is a definitive sample of his creativity.

In which Han goes slumming with a punk guitarist. Not improbable, since some of the Dutch out-jazzers have been known to co-mingle with open-minded rock cats in search of new improvisational scenarios. And Han will play duets with anyone game enough to take the chance. Terrie Ex functions as a third-chair Derek Bailey: spartan axe-amp setup, slightly distorted, wrestling fragments of sound from his guitar. While there is an arcane method to Bailey’s madness, Terrie is clearly just “making noise” here, going for random dissonance, bent strings, percussive jabs, whatever. But no one in their right mind is buying this for the guitar; Terrie’s hazardous contributions are just walls for Bennink to bounce off of, thrusts for him to dodge...and how does he get those many sounds from his kit?

The duo converses in abstract ways, either through rhythmic rejoinders or textural responses - metal versus string, skin versus slide or what have you. The 17 improvs include several brief encounters and a couple of lengthier pieces that actually establish a mood or two. Bennink’s rhythms are of the additive variety - percussion as lifebeat dance, not doled into fours or theme/variation. Not for anyone but fans of the drummer, who’s in top form throughout.

|