|

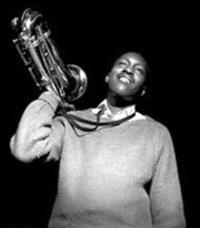

Tenor saxophonist Hank Mobley wasn’t the pioneer that some of his peers were, but his smoothly toned, concise style earned lots of praise over the years. While Mobley served well as an employee of Miles Davis (my first exposure to him), I think Miles’ quintets worked best with a more exploratory saxophonist; on the other hand, Mobley’s solos hit me like a breath of fresh air on Johnny Griffin’s triple-tenor Blowin’ Session album, where Griffin and John Coltrane fire the heavy ordnance. Plentiful sideman gigs aside, I had to wait until spinning a few of his own albums to really appreciate Mobley’s voice. Soul Station Feb. 1960 / Blue Note RVG I would assume this record makes many a shortlist of definitive Blue Notes, given the enticing material and swinging foundations from Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers, and Art Blakey that inspire exemplary tenor sax from Hank Mobley. His phrasing garnishes mainstream grammar with melodic poise that at its best seems premeditated to perfection, and since Mobley’s the only horn, Soul Station shines plenty of wattage on his subtleties. First up is a cheerful version of Irving Berlin’s “Remember” that features an outstanding Mobley solo. Perfection in jazz (as I referred to above) is usually inaccurate word choice, but when improv is so well executed as to invent a new song within an existing one, what other description suffices? The original “This I Dig of You” has a catchy melody and vamp that switches to steady-time solos; Kelly scouts first to clear a path for Mobley, whose ebullience extends to Bud Powell’s “Wail”, and Blakey gets a quick spot. “Dig Dis” (as opposed to “Dis Here” or “Dat Dere” – ah, Blue Note ebonics) hits a standard 12-bar blues with Mobley alternately yearning and tinkering.

In “Split Feelins”, the suggestive piano chord and Latin vamp directly anticipate Joe Henderson’s “Mamacita” – later to appear on Kenny Dorham’s Trompeta Toccata – though “Split Feelins” soon reveals itself a straight swinger at heart. The title track delivers on its pledge of soul yet the performance comes off a bit monotonous. The closing standard “If I Should Lose You”, while decently done, is less forceful than the version on Roy Haynes’ 1962 LP Out of the Afternoon, despite the pointlessness of comparing Roland Kirk and Hank Mobley – or Kirk with anyone, for that matter. In any case, this is an excellent album with staying power.

Roll Call adds trumpeter Freddie Hubbard to the Soul Station lineup of Mobley, Kelly, Chambers, and Blakey and is generally a more aggressive record. The leader puts forth many confident moments, and I would rate Hubbard’s showing as one of his best as a hired gun. Also, Wynton Kelly happens to be more amenable to me in Mobley’s sessions than he is under Miles Davis’ name, maybe because different drummers are prompting him. I also credit the varying timbres of different jazz groups, where an instrumental voice shines more or less depending on its surroundings – not an uncommon phenomenon.

The title track is fit to satisfy any hardbop jones (including lengthy horn statements and a Blakey solo that seems freer than usual for him) and so is “The Breakdown”, a taut blues with Mobley quoting “Bemsha Swing” during the drum exchanges. There’s further fuel in “My Groove Your Move”, “The More I See You”, and the catchy “Take Your Pick”. The stop-time testimonies in “A Baptist Beat” prove once again that explicit ‘gospel’ jazz is often a stilted mismatch, but the track loosens up over the long haul. (The alternate take is worth a listen too, though I’m not waiting for a Catholic Conga, Presbyterian Passacaglia, or Methodist Montuno anytime soon.) For me, the quartet format of Soul Station is more conducive to studying Mobley’s style, though he’s equally on form here, as is everyone else.

A fruitful workout indeed for Mobley, guitarist Grant Green, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers, and Philly Joe Jones at the drums. The assertive title piece gets the album down to business right away, Mobley lacing numerous motifs into his solo and Green white-knuckling the edge of Jones’ drumming, which gives the soloist a milliseconds-wide window of swinging in the strongest possible manner. A proper analysis of the 32-bar “Uh Huh” would note how the first three bars deke the listener into a 12-bar frame of mind while the remaining measures deviate from those expectations. I love the uncanny blend of Mobley and Green’s tones in the theme, and when Philly Joe locks into his rim-click groove beneath the solos, everything’s golden. “Smokin” follows as a true blues, uptempo with energetic trades at the end.

As if the first three cuts didn’t lift enough spirits, “The Best Things in Life Are Free” makes a joyous turn to outside material. Mobley cites “Four” during his solo, and believe me, I’ve refrained from naming several other clever quotes on his albums that the liner essays don’t. The relaxed blues “Greasin’ Easy” finishes the original program, and the CD appends “Three Coins in a Fountain”. As a blowing session with hooks galore, I give Workout high marks, and I’ll even accept Mobley’s occasionally squeaky reed as giving his sax a random sonic edge here.

More than a few Blue Note reels had to wait a decade or two before being released; Another Workout first appeared in the mid-1980s and then received RVG CD treatment in the following century. After reading much acclaim for this date, I added it to my Mobley curriculum, but it doesn’t live up to my expectations. The playing is fine, the sound a little odd, but mainly, the album doesn’t carry the weight of the others Hank recorded around this time. One sure highlight is Mobley’s lovely reading of “I Should Care”, and “Hello Young Lovers” nods to Miles Davis’ Prestige-era approach to standards – perhaps appropriate since Mr. PC and Jones are on hand again. But “Out of Joe’s Bag”, despite Philly’s lively drumming, comes across somewhat trite, and “Hank’s Other Soul” turns a promising theme into an unmemorable morass. Hank scoots nicely though the modal “Gettin and Jettin” but the track pales next to its remake as “Up a Step” on No Room for Squares. This session was certainly worth pulling from the vaults and maybe it’s as special as other listeners attest, but I don’t hear that wonderfulness in full.

I’d owned Soul Station beforehand, but this was the first Mobley album that really hooked me; a couple of the tracks caught my ear in a record store (long live brick and mortar) and I liked it even more on further listens. I wouldn’t say it’s better than the above titles, just slightly more modern in scope, and it features an array of players from two different sessions – Lee Morgan/Donald Byrd (trumpet), Andrew Hill/Herbie Hancock (piano), John Ore/Butch Warren (bass), and Philly Joe Jones (drums).

The modal tunes “Up a Step” and “No Room for Squares” both swing infectiously with Mobley in sharp form. His tenure with Miles Davis surely helped spark these numbers, and notice how Hank teases so much out of just a handful of pitches in the first bars of his “Squares” solo. He’s just as hip when surfing standard chord changes in “Three Way Split” and “Old World, New Imports”, two upbeat tunes in which Philly Joe also distinguishes himself. The ballad feature is “Carolyn”, a pretty if not especially deep Morgan composition with nice sax counterlines. The album makes room for one square in Morgan’s “Me ‘n You”, a corny boogaloo that doesn’t match the tone of the other pieces. Nonetheless, “Three Way Split”, “Up a Step”, and “No Room for Squares” earn the disc an enthusiastic endorsement.

|