|

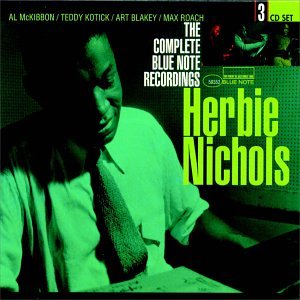

A fine pianist and truly original composer, Nichols remained obscure during his time. He died of leukemia in 1963 at only 44 years of age. Fortunately, a fair sampling of his music survives and has gotten belated attention from various modern artists and from listeners seeking something a little different. The Complete Blue Note Recordings May 1955-Apr 1956 / Blue Note The Monk comparisons are correct in a general sense: here’s a forward-thinking pianist who created his own sphere of music, who realized his early blueprints in trio recordings, who injected standard changes, forms, and rhythms with new ideas, who made the abstract sound accessible. But Nichols never had the chance to match Monk’s career, as his life was cut down prematurely. This valuable set encapsulates his legacy, documents what was and perhaps what could have been. It’s as if Nichols started with general song templates and gave them all a good elbow in the ribs - an extra bar or two here, an altered cadence there, and ingenious figures everywhere. Notice the “giant steps” chord movements of the “Third World”, the ambiguous voicings of “Double Exposure”, and the chromaticism of “2300 Skiddoo”. These little elements appear ahead of their time, as if Nichols was predicting in miniature the stylistic specialties of 1960s players. Herbie’s piano style is in turn boppish, classical, halting, joyous, and unsettling. He tends to avoid linear excursions, preferring to move through tunes a block at a time, building an overall statement in piecemeal fashion. (He will sometimes embark on a long melodic line, although his self-accompaniment can steal attention from it.) His left hand slips into subliminal stride or drops low register bombs, while the right completes the spectrum with high sprinklings and tinklings. Then the hands will meet somewhere in the middle register for syncopated dissonance or entangled bop phrases. In a nutshell, his playing is both old and futuristic. As with Monk in the past, and Andrew Hill in the future, Alfred Lion took a listen and wanted to record everything Nichols had. He lined up a few trio sessions, the results of which were issued on a couple of different discs. Decades later, Mosaic assembled the complete Blue Note recordings, and when that specialty set went OOP, Blue Note themselves decided to issue this 3-disc collection (in 1997). On these trio sides, Nichols is aided by crafty rhythm players who glide through the difficult nooks and crannies of his tunes. The bassists are Al McKibbon and Teddy Kotick, and on skins, there’s Art Blakey and Max Roach, both vital to early Monk recordings as well. The drummers not only have the twisted forms to negotiate, but Nichols allots many drum breaks in his tunes, either as intros or sudden detours in the middle or at the very end of the form. Many of his tunes end with a 4 or 8 bar drum signoff. May 6 and 13, 1955: Al McKibbon and Art Blakey push along a delightful first series of tunes. “The Third World” is an appropriate opener, given the conspicuous chord movement that sounds modern (roots moving by thirds) yet classic at the same time. “Step Tempest” continually renews a cycle of tension and unexpected resolutions. There is humor in the intro to “Blue Chopsticks” and also in the ragtime of “Cro Magnon Nights”, yet none of the music is really lighthearted. Both “Blue Chopsticks” and the brisk “It Didn’t Happen” hammer at chords with dissonant intervals, sending shockwaves though the systems. “Brass Rings” features a dense, ascending harmony, while “Amoeba’s Dance” is an inscrutable etude with off-center bass bits. “Double Exposure” states a soft, falling line, lets it fall again from a higher precipice, and then drops a couple of chords with pre-Tyner voicings to open up new vertical implications. The bridge is even more uncertain. My favorite track is “2300 Skiddoo”, a sly number with a winding melody that gets varied in each iteration. The rhythm duo complements the piano by playing in (what feels like) halved time, creating (along with the melodies) a sense of expectancy that never dims. The upbeat “Shuffle Montgomery” follows the same tactic of repeating a main line with variation, the final bar of which is reversed for the bridge. It should be mentioned that nowhere in these Blue Note sessions does Herbie write any sort of blues or ballad - most of his tunes are based on the AABA form or something more original. August 1 and 7, 1955: McKibbon’s still aboard, and Max Roach takes over the drum stool for a dozen tunes that range from laid-back ambles to hectic swing. “The Gig” is perhaps Herbie’s most unusual piece, a massive 70-bar form that moves in fits and starts and reaches a frantic climax. The release point is a series of chords descending in minor thirds, a cadence Chick Corea would emphasize on his Now He Sings Now He Sobs album. I don’t want to say Corea stole Nichols’ idea, but the effect is similar. Another tricky tune is “Applejackin”, explored in three takes. Less tricky and also appearing in three takes is “Furthermore”, the tempo different each time. “Lady Sings the Blues” became a full-fledged song when Billie Holiday added lyrics, yet the prototype has its own ruminative quality. Over a midtempo gait, Herbie takes a very Monk-like solo, decorating the melody with thickened chords, trilled teases, etc. The harmonic uncertainty continues in “117th Street”, as melancholic descending chords are periodically broken by little uplifts, and there’s a rare bass break. Not even the easygoing “Sunday Stroll” is free from ambiguity; in fact, it’s a stern blend of shade (the chord voicings) and light (the happy closing cadence). “House Party Starting” has a lot of suggestive space between the nonchalant melody line and the tolling accompaniment. Both “Hangover Triangle” and “Chit Chatting” are at a manic pace; the former boils over after a Max solo. The urgent character of “Chit Chatting” (not idle) is underscored by ominous counterlines. “Nick at T’s” turns a six-note motif left and right in a harrowing corridor, finally escaping into a bridge sprint and drum release. “Terpsichore” dances on bright cymbals from Roach, and “Orse at Safari’s” is another unsettling uptempo swinger. These two August sessions produced a wealth of original music that sounds like nothing in contemporary jazz of the time. April 19, 1956: The final session features bassist Teddy Kotick and Roach. There are a couple of less than compelling tracks here - the obscure “Wildflower” and the Gershwin ditty “Mine” - though the remaining pieces are among Herbie’s most effective. I used to think “Trio” was a generic reference to the personnel, and then it became apparent that the piece features three distinct musical ideas. “Spinning Song” makes a point of thematic development, while “Riff Primitif” taps Nichols’ gift for foreboding atmosphere. “Query” asks and answers a melodic question. As with all the previous sessions, these tunes are heard in master and alternate takes. The alternates sometimes have small miscues, but for the most part they’re true second runs with no drop in quality. The trio format allows us to appreciate Nichols’ compositions, yet one wonders what they might have sounded like with a lead voice (Sonny Rollins would be my choice), and how Herbie would have played underneath a horn. The tunes would have “sung” more, and might have had more flexibility. Yet these trio sides all tell stories. Later musicians such as Misha Mengelberg started performing and recording Nichols’ music in quartet and quintet situations. It’s a shame Nichols departed so early, and maybe it’s a small justice that others are disseminating what he left behind.

The sound of the recordings is pretty good, notwithstanding occasional tape wear. The booklet in the BN box has a couple of great essays, including the original liner notes by Herbie himself. Maybe Blue Note will eventually reissue the original 10” and 12” titles, but I think that’s a moot point, because anyone who enjoys some of Herbie’s BN tracks will surely appreciate all of them, and this box is a handy way to acquire them.

|