|

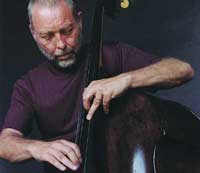

English bassist Holland got a jumpstart with Miles and went on to a number of musical associations, from traditional to free jazz. In the 1980s, he became a steady bandleader and also a first-call sideman, appearing on countless records. (Much like his occasional mate Jack DeJohnette.) Conference of the Birds Nov. 1972 / ECM One of the best progressive jazz records ever made. The forward-looking players on this date - Anthony Braxton and Sam Rivers on reeds, Holland and Barry Altschul on bass and drums - had all worked together previously in one way or another. What they’re given to work with are six rousing Holland themes that spur creative free associations. You’d be right to note the instrumental lineup and think of Ornette’s early quartets, and that certainly is a reference point. However, they take the shape of jazz to come much farther, with superior horn work and flexible rhythms. All four musicians have equal voices: Altschul’s kinetic percussives are as tangible as the outgoing reedists, while Holland’s bass is never far from the foreground, either. Two tracks get blue ribbons, the first being “Four Winds”, which has a geometric yet flowing theme. The phrase and bar lengths are more convoluted on paper than they sound to the ear (and under the fingers), and it’s one of your humble narrator’s favoritest melodies anywhere. In the improv, Braxton’s soprano solo takes off into the stratosphere as Holland and Altschul burn below. The other standout is the title track, a folk-like reverie introduced by a bass solo and followed by flutes in odd-metered song. Marimba replaces cymbals as the track gets ever more prayerful. It’s one of those pieces of music that feels like it had to be written and grace this planet - if not by Holland, then by someone, somewhere. “Interception” and “See Saw” follow the “Four Winds” model of angular head, fast swing, and fervent solos from the sax men. It’s interesting how the solo baton is passed on these pieces: the first soloist is joined by the other horn at the end of his solo, then the two play simultaneously for a short while, then the tune’s theme is recalled by both. The second horn then takes a solo, with the first soloist returning the duet favor before the theme appears yet again. “Q&A” begins with a percussion solo, where Altschul plays woodblocks, bells, and a ratchet in addition to the usual trapset. The horn theme is a question and answer, and the ensuing group conversation is the loosest of the album. “Now Here” breathes the same solemn air as the title track, but it’s a bit riskier, especially in the microtonal flutes.

There are several reasons to hold the album up as a Great One. It delivers on the free jazz promise, it’s an example of Holland’s extraordinary writing and bass playing, it’s an all-acoustic “relic” from a mostly electronic decade, and it balances individual and collective identity. More best-of lists should mention it.

Gateway is a three-way democracy of John Abercrombie (guitar), Holland (bass), and Jack DeJohnette (drums, etcetera). The trio released two spacy albums for ECM in the ‘70s and then decided to knock heads again in the mid-90s. The tune-oriented Homecoming was the first release from a session that also bore the freer In the Moment. The former is a modern jazz album that’s neither traditional nor falls into a fusion bag, notwithstanding the occasional backbeat or distorted guitar. Abercrombie sweetens his guitar tone with light chorus, and his tasteful phrasing makes use of a volume pedal. Holland has lots of room to roam, and DeJohnette slithers around in a punchy way. The best material comes from Holland: the stirring major-key theme of “Homecoming” seems to go in several directions at once, followed by open solos, and “How’s Never” is a strutting, stumbling jazz-rocker in 7. Abercrombie builds to heated peaks in both, and Jack’s thunderous, “sloppy” solo in “How’s Never” is great. There’s also friendlier stuff like “Calypso Falto” and a couple of tracks that lean toward the dreary, but the main attraction of Homecoming is the sound of the band and the chemistry they share. Chemistry allows the offhand improvs of In the Moment to happen. The title track and “Cinucen” lock into tight ethnic grooves (with Jack on either Korg Wavedrum or frame drum) that allow Abercrombie to explore exotic intervals. “In the Forest” wanders with no compass, while “Shrubberies” is a more fruitful venture into free foliage, where Holland’s ominous bass, Abercrombie’s fabrics, and Jack’s rumblings reach a couple of small climaxes. Why cut off the feedback just as it was getting good, John? Did Manfred shoot you a look from the booth? In the Moment ends as Homecoming does with a light etude featuring Jack on piano.

Overall, the organic vibe of these records keeps them from feeling dated or indulgent in any way. Intelligent players, satisfying results. Indispensable for fans of the guitarist, I’d say.

At the time of writing, the Dave Holland Quintet is one of the more original working units on the scene. Some of their musical genetics can be traced back to Holland’s 1995 quartet album Dream of the Elders, which mixed long folk melodies with stylish basslines, while 1997’s Points of View introduced the quintet formation and Holland’s new plan of attack. Points of View is a really fine record, but Prime Directive is their definitive work in my opinion, and it cements what became an instant classic lineup: Chris Potter (saxophones), Robin Eubanks (trombone), Steve Nelson (vibes and marimba), Billy Kilson (drums), and the leader on bass. The music retraces the lines and angles Holland has been drawing ever since Conference of the Birds and puts them in a modern context. The criss-crossing trajectories of the horns and vibes outline space rather than fill it, underlined by Kilson’s pocket drumming. Holland’s basslines are the elliptical cycles of motion at center. The ensuing aural web is, like a spider’s, organically and evenly constructed, fragile yet resilient, and effective in every quarter. Tracks such as “Seeking Spirit” and “Juggler’s Parade” entwine off-center bass ostinatos, marimba patterns, and horn melodies (in staggered counterpoint) and are thus multi-centered, each player shouldering a specific component of the whole. Polyrhythms abound, and when one soloist breaks away, the band re-arranges its support mosaic. The improvisations aren’t very “out”, yet the lack of a chordal instrument (not counting Nelson’s malleted intervals) means that harmonies are transient, or at least implicit. The players prove trustworthy with the freedom and there are fine solos from all. The title track is simply incredible, a sequence of syncopated riffs and melodies with a flexible beat underneath. Potter and Eubanks solo together, not trying to call and respond, or harmonize, or start and end their phrases at the same time, but simply pulling off simultaneous solos that are bound in feel and spirit. It’s a pretty amazing feat, and they do it again in the later “Wonders Never Cease”. (An apt title.) Anyway, as they’re burning together in “Prime Directive”, Holland and Kilson cook up some magic of their own. The track ends with staccato signals and Kilson’s quiet hi-hat/rim click pulse - so very cool. Breaking up the group’s usual modus operundi are a couple of subdued ballads and Potter’s complex “High Wire”. The album ends on a somewhat humorous note with “Down Time”, where Eubanks plunges wah trombone over old-style bass and brushed drums. It’s pretty clear, once the tune starts modulating and Eubanks digs in, that it is a love letter to older jazz. I think it’s a great gesture to put something like this on the album, and it’s a totally enjoyable tune in itself, so bravo.

Detailing the rest of the album would take a while, so suffice it to say that Prime Directive is a great place to check out the Holland’s Quintet original sound. Let me add that Billy Kilson is much more palatable than a lot of hyperactive backbeat drummers.

In which the Holland Quintet continues their brave adventures. Well, “brave,” I dunno, they sound like they’ve found their comfort zone, but more power to them. Why fix what isn’t broken, or yet worn out? Holland has always known how to write in a modern style without breaking ties to the past, and so the title track hints at Mingus and “Cosmosis” updates hardbop. Other tunes have no obvious lineage. Check “For All You Are”, a sensual, dynamic ballad, or Billy Kilson’s “Billows of Rhythm”, a funky blast of not-quite fusion that could never have happened in the ‘70s. So integrated is the group’s playing that individual moments are hard to isolate, but one might note Kilson’s shimmering cymbal work in “Go Fly a Kite”, the pairing of soprano sax and marimba on “Shifting Sands”, or Eubanks’ brawny trombone statement in “Global Citizen”. Holland takes some fine solos as well.

The album doesn’t really make (m)any advances on what we’ve already gleaned from its two predecessors, yet it’s still a fine example of the quintet in action. The actual recording, however, starts to keep the instruments a little too far out of reach. I’m all for the sonic range that was heard on Prime Directive, but Not For Nothin’ spends more of its time on lower levels that muffle the band’s impact. The same can be said about the group’s Extended Play live album, the sound of which is too remote for a club gig.

ECM’s Rarum series allows the label’s marquee artists to assemble their own best-of collections. The packaging is minimalist and handsome, and the remastering provides a little upgrade to what are usually fine recordings to begin with. Holland’s Rarum samples a number of his albums, and a track by track breakdown will let us trace some of his artistry over the years. The set begins with “How’s Never” from Gateway’s Homecoming album. This funk/rock/jazz jam starts with a quiet bassline and eventually boils over. Abercrombie’s guitar solo has some distorted angst, but the track never loses its cool, except when DeJohnette explodes in his drum solo. “You I Love” comes from the semi-traditional Jumpin’ In album of 1983. The tune’s complex theme leads the horns (Kenny Wheeler, Steve Coleman, and Julian Priester) into conversational moments, a la Mingus. Like everything else on the compilation, this track has no piano; Holland prefers getting his harmonies from vibes, or guitar, or stacked horn notes. “You I Love” might be called neoconservative jazz, except Holland never worried about what was “real” jazz or not, and his music remains true to itself. The cello solo “Inception” dates from 1982. Holland dips adeptly into both classical and blues vernaculars. “The Balance” heralds the late ‘90s Dave Holland Quintet. It begins softly and gradually increases in texture and volume as the band unveils their interplay. There’s a true balance to everyone’s contributions as they assemble an integrated musical scaffold. It’s from the excellent album Points of View (Not reviewed above, but as worth hearing as Prime Directive.) Before the Quintet was the Dave Holland Quartet and their Dream of the Elders (1995), which blends some nice folk-like melodies with nifty rhythms. The somnambulant “Equality”, a droning number with a Maya Angelou poem intoned by Cassandra Wilson, does not represent that album very well, and it’s really the only dull moment of this Rarum disc. I would have picked the “Dream of the Elders” title track, a great piece that previews the upcoming sound of the later ‘90s quintet. “Nemesis” is from 1989’s Extensions, with Steve Coleman (sax), Kevin Eubanks (guitar), and Smitty Smith (drums). It has a jagged rock backing, a wailing Eubanks solo, piledriving drums, highwire bass, whining sax, and so on - a solid example of the Extensions sound. “Shifting Sands” is from the DHQ’s third album, Not For Nothin’. Marimba, soprano sax, and trombone entwine in a melody so soothing you wouldn’t notice it’s in the odd meter of 9. Holland and Steve Nelson (on vibes) take nice solos. “Four Winds” is not the classic take from Conference of the Birds but rather a trio rendition by Steve Coleman, Holland, and Jack DeJohnette. Their Triplicate (1988) is decent but sounds a bit empty, as Coleman’s alto leaves a lot of frequencies uncovered. The trio do okay by “Four Winds”, though it lacks the energy of the 1972 version. “Prime Directive”, from the 1998 Quintet album of the same name, is just a badass track, as I’ve said in a previous review. “Homecoming” was better done by the Gateway trio in 1994; this 1984 version (from Seeds of Time) has more of a street parade feel with horn dialogues between Coleman, Wheeler, and Priester. I wish this track and a couple of others on the collection were recorded more directly. Jazz doesn’t need to be miked at a distance and awash in reverb.

The disc’s finale is the meditative title track from Conference of the Birds. I don’t know how well it sits as an album closer - it really leaves the listener hanging - but it certainly belongs on any collection of Holland’s best work. Overall, the Rarum CD captures Dave’s creative scope, while the original albums tell the fuller story.

I saw Dave Holland’s sextet in concert early in 2007, and they’re all present on this studio album - Antonio Hart (alto sax), Robin Eubanks (trombone), Alex Sipiagin (trumpet), Mulgrew Miller (piano), Eric Harland (drums), and Holland on bass. Much of their music resembles that of the preceding quintets, albeit brassier and fuller thanks to the trumpet and piano. Some of the tunes have been heard before, too, like “Lazy Snake” (from Dream of the Elders), “Equality” (from the same album, still a dirge-like tune but benefiting from the addition of piano), and “Modern Times” (from Gateway’s Homecoming.) Anyway, most of the tracks have a fresh sound, even though Holland’s bass strategies and the overall vibe of the arrangements is nothing new. “The Sum of All Parts” is made up of contrary lines, off center riffs and drumbeats, and so forth - typical of the style of Holland’s recent groups, but still remarkable. The multi-part “Rivers Run” puts the spotlight on different soloists before concluding with a brisk full-band theme. “Fast Track” is a modern bop piece in which Miller steps to the fore, while “Double Image” goes for a driving big-band sound. “Processional” summons a lovely landscape before the groovy finale “Pass It On”, powered by an cool bass riff and more exuberance from the horns.

This is an accomplished group - Hart’s a passionate player, Eubanks is the premier trombonist of the modern scene, and Harland dissects the beat as well as any of the previous drummers in Holland’s employ. Holland remains one of the most complete jazz bassists in history. The sextet plays tightly and the music is excellent, but then again, it feels a little like diminishing returns. I say that with full respect of the special small-band style Holland has developed over the years, but Pass It On essentially treads the same ground as something like Prime Directive, only with a few different musicians and melodies. I’m also a little wary of the mix, which is good for the most part but turns the snare drum, of all things, into a plastic coffee-can lid bonking away in the background. Nonetheless, this is a four-star record, worth a listen if you haven’t heard Holland in a while.

|