|

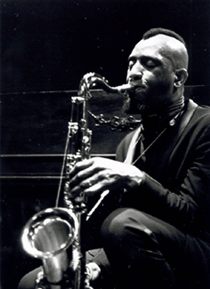

THE tenor sax giant, after Pres and Hawk (who were his early idols). Rollins’ ability to structure spontaneity in his solos is astonishing. He’s at his best in standards or originals that utilize standard progressions where he can develop themes over an established template. Strangely or not, this doesn’t translate to free music - Sonny never sounds completely comfortable in his freer 1960s efforts. He needs a tune to get going. Nor does he bother much with group interaction, which is kind of disappointing, but when a player has a message like Rollins, he can take the elevated pedestal and I’ll hear him out. We’re talking about one of the greatest improvisers ever.

Rollins’ in-the-moment genius is a performance-based phenomenon, and he thrives or dies by the inspirational sword on stage. Harnessing that glory in a recording studio is tough to do, and Rollins sometimes voiced dissatisfaction with his own recordings. Nevertheless, several titles below show what Rollins was capable of when the mood and tune were right.

This disc combines early Rollins dates, of which only four tracks (the later ones) feature the MJQ men. “The Stopper” has some of the famed counterpoint of that quartet as Sonny dallies above them, while “In a Sentimental Mood” is, well, sentimental and straightforward. Sonny’s best solo comes in “No Moe” with every phrase either initiating or completing a fresh idea. These tracks, like everything else on the disc, stay within the 2-3 minute range and force the players’ hands. Rollins, known for lengthier constructions, manages to tell logical stories within brief windows, and Milt Jackson’s vibes are one of the most joyous, flowing sounds in all of jazz. The December 1951 date is with Kenny Drew, Percy Heath, and Art Blakey, and it contains more balladry, bop, and blues over the course of eight tracks. Rollins contributes three originals, including the tropical “Mambo Bounce”. In terms of solo development, notice how Sonny keeps referencing the theme of “With a Song in My Heart” during his improvisation on same, grabbing phrases from it and pointing them in different directions. His later, more extended thematic permutations can be traced to this early infatuation with malleable melodies.

The disc ends with “I Know” (= “Confirmation”), a themeless runt from a Miles Davis session where Miles insisted that Rollins get a moment in the spotlight, and thus it became Sonny’s “hello” as a leader. This trivia is more memorable than the performance itself, but for the rest of the CD? Well, would you want to read what Shakespeare wrote as a younger man?

Sax-god-in-training Rollins turns in one of his best early performances on this aptly titled album, with Kenny Dorham on trumpet and the rhythm section of Elmo Hope, Percy Heath, and Art Blakey. Both the title track and “Swingin’ for Bumsy” charge forward with no hesitation, and Sonny’s solo on “Moving Out” is so well ordered and executed as to rank with his more celebrated playing soon to come. Dorham flashes his chops on these tunes as well, and credit Blakey for swinging the drums without a hi-hat. The mood relaxes in the trumpet-less ballad “Silk ‘n Satin”, where Sonny milks the chord changes as only he can do, and “Solid” brings the groove back up for a hardbopping blues. These four tracks come from the August session, while “More Than You Know” comes from a later meeting with Thelonious Monk. This lengthy ballad is notable not just for Sonny’s passionate lines but for Monk’s relatively “normal” playing as sideman. (“More Than You Know”, along with two others from the same session, is also available in Monk’s complete Prestige boxset.) Though not as fully developed as his 1956-7 records, Moving Out stamps some of Rollins’ strongest traits into place and makes an enduring listen, especially in the fine RVG remaster of 2009.

In which Rollins stretches out in the company of Ray Bryant, George Morrow, and Max Roach. The material includes the bouncy original “Paradox” along with Strayhorn’s “Raincheck” and an ostentatious trouncing of “No Business Like Show Business”. “It’s All Right with Me” burns along and threatens to fall apart after the sax-drum exchange in its final minutes. Speaking of, these aren’t your typical traded fours; Bryant and Morrow drop out whenever Sonny and Max start swapping bars, as if they see no point in intruding. Elsewhere, Max plays frenetic shadow to the saxophonist, while the piano and bass make little difference to the music except in the ballad “There Are Such Things”. Otherwise, they just fill the sonic frequency between tenor and drums. Rollins says a lot in his solos, and even though he still pulls phrases from the communal bop thesaurus (and is a bit gliss-happy), his sentences and paragraphs sometimes produce a majestic axiom or two. As “Such Things” indicates, he has plenty of ideas to get out. Relative to his peers, Sonny was already half a giant, and he would get even better with time. Rollins archaeologists won’t be disappointed with this one.

Sonny’s stint with the Brown/Roach Quintet apparently gave someone the idea of letting those gentlemen be Sonny’s sidemen on this session, so here they are: Clifford Brown (trumpet), Max Roach (drums), Richie Powell (piano), and George Morrow (bass). This is one of the rare early instances where Rollins deigns to bring another horn on board for his own session, and the jousting between trumpet and tenor pays off. They exchange the melody phrases of “Kiss and Run” with mischief (what sounds like the beginning of Brown’s solo is actually Rollins’) and both men play inspired solos whenever they step up to the mike. Brown is super agile in “Kiss and Run” and “I Feel a Song Comin’ On”, and he starts every chorus in “Pent-Up House” with a perfectly stated melody. Sonny breathes free in “Count Your Blessings”, which Brown sits out, and “Valse Hot” detours into 3/4 time. On the other tracks, the watertight rhythm trio swings hard and lets the shiny horns do their thing. Essential.

Borrowing the Miles rhythm section - Red Garland, Paul Chambers, Philly Joe Jones - and as a guest on the title track, John Coltrane. Not quite a competition, “Tenor Madness” showcases the two tenors in a 12-bar blues. Both take long solos and then trade phrases. No matter how many notes Coltrane tosses off, Sonny answers with the overriding power of a well-sculpted melodic line. That’s not to disparage Coltrane, who was getting his awesome technique together at this time, but Rollins is far more to the point and wiser with melodies. If you want a distinct synopsis of their differing styles, check out “Tenor Madness”. Apart from that, it’s just a twelve-minute blues. The rest of the album is reduced to quartet. Sonny echoes Coleman Hawkins in “My Reverie” and plays with ease over the standard chord changes of his own “Paul’s Pal”. “When Your Lover Has Gone” features more of the Hawk vibrato and some old school scooped notes. “The Most Beautiful Girl in the World” starts her day waltzing, veers into a short tenor daydream, and then Philly Joe bumps her into a purposeful 4/4. Sonny’s brief solo is full of repeated ideas. He likes dropping lines twice in a row, just to see how they sound over the shifting chords. If you start with a solid melodic premise, why not see where it goes?

Despite some delights, the four quartet tracks are a little restrained. The title track is looser, because Sonny was contouring his playing in response to the two-tenor scenario. So it’s a secondary Prestige at best, good as a quick intro to the ‘50s world of Rollins, or as a supplement to its successor.

Mark this as one of the best jazz albums ever. Top 10. Inasmuch as jazz is a fleeting process, along with Sonny’s unpredictability and stated preference for live playing versus studio, there’s an irony in trying to tie this musician to a particular recording. No wonder Rollins bristled a bit when Gunther Schuller wrote an academic analysis of his “Blue 7” solo. The fact remains that Colossus is an outstanding forty minutes of jazz, still fresh half a century later, so thank goodness for the Van Gelder studio. And despite all the gigs and albums that came after it, it remains Sonny’s most essential. Or so I say. For one thing, the tunes are immediately catchy. Who can forget the joyful “St. Thomas” calypso, or the sultry curtain rise of “Blue 7”? The knife-macking theme of “Moritat” was already emblazoned in the subconscious, and it seems that most advanced improvisers tackle “You Don’t Know What Love Is” sooner or later. The boppish “Strode Rode” is memorable for its rhythmic accents, which Max Roach recalls in his drum breaks on that piece. Yeah, Max is back, swinging with Tommy Flanagan on piano and Doug Watkins on bass. The K2 remaster of 1999 brings up Watkins and reveals just how important his rock-solid walks are to the music. Roach is featured heavily in solos and exchanges, and the album is almost as definitive for him as it is Sonny.

Silly as the album title might be, Rollins delivers on the boast, not in riproaring assault, but in melodic surety. What prompted Schuller’s essay was the extraordinary consistency of the “Blue 7” improvs, from the opening intervallic cell through the themes and variations that the tenor develops until the end. Of course, that’s what other soloists have done before and since - find a thread and follow it - though Sonny’s instincts were sharper than the norm for this piece. The tenor solos (split around Roach’s drum solo) are clear enough for a beginner to follow, and succinct enough for the seasoned listener to really appreciate, vis-a-vis the ideal of stripping away extraneous tangents and getting to the melodic heart of things. Sonny gives every piece handles to grasp, be it the clipped motifs of the “St. Thomas” solo or the twists in “Strode Rode” or the cadenza of “Moritat”. Most of his playing here sounds premeditated, but of course it’s improvised, and that’s the marvel of it. Max also uses leitmotifs for his solos, and his drums are as musical as any other instrument in the group. I could rave on, but you saw what I said at the start, and there is little left to say for such a peak album.

As a tribute to Charlie Parker, Sonny concocts a 26-minute “Medley” of seven songs associated with Bird, including “My Melancholy Baby”, “They Can’t Take That Away From Me”, and “My Little Suede Shoes”. Trumpeter Kenny Dorham and pianist Wade Legge share the spotlight with Rollins, each leading a couple of tunes by themselves, and everyone comes together on “Star Eyes”. It swings nice and easy thanks to George Morrow and Max Roach, but with only one Bird original in the mix, and a playing temperature that rarely rises above warm, this suite seems only casually connected to Parker’s legacy. Then again, three of these participants had played with Parker, and perhaps they preferred to reflect rather than replicate. The Rollins complete Prestige box divides the medley into separate components, while this single RVG keeps it as one big track. That’s no burden, as the tunes flow easily from one to the next, so just sit back and enjoy some melodies of yesteryear.

The remaining pieces “Kids Know”, “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Your Face”, and “The House I Live In” don’t raise the intensity much, but Rollins dishes out some great tenor sax. He careens around the waltz beat of “Kids Know” (which otherwise seems a repetitive rewrite of “Valse Hot”) and has no problem with the slow, romantic “Accustomed”. Rollins plays “The House I Live In” passionately, constructing one of his best solos of the period even though the tune itself is a bit mundane. “House” was not included on the original vinyl LP due to time limits, and it’s nice to have it back where it belongs. Since Plays for Bird is such an easygoing album, I wouldn’t put it in the front line of Sonny’s Prestiges, but it complements the more aggressive albums like Plus 4 or Colossus, and the “Bird Medley” is pretty unique. Good sound on the 2008 remaster, too.

The hokey melodies and woodblock horse-hoofing of “I’m an Old Cowhand” and “Wagon Wheels” are corny at first listen, but anyone who’s heard these tracks before will greet the introductions with a smile, for they know the wonders that Sonny is about to unleash. And what about the cover photo? If the hulking Colossus didn’t get ya, the Gunslinger will. Backed by Ray Brown and Shelly Manne, Rollins makes the tenor trio format sound much more natural and commonplace than it actually was at the time of recording. The music takes on a Western theme, with a couple of urbane ballads (“There is No Greater Love”, “Solitude”) for variety. Sans piano, there’s an appropriate feeling of space in every piece, the better to let Sonny’s phrases linger in the ear. As with Saxophone Colossus, he crafts and distills every line to a fine point. Everything you’d want to hear from his horn in this era - the bop squiggles, the self calls and responses, the opulent ballad phrases, the thematic awareness - is here, along with a dusty drawl and other sax inflections suitable to the material. Two originals: “Come, Gone” is much in the “Airegin” or “Paradox” bag, and “Way Out West” is a successful mock-up of the wagon-wheel vibe. Brown and Manne amble along these trails at a steady, relaxed gait. This is one of the very best Rollins albums, and in the 20-bit remaster from 2000, the sound is excellent.

On a personal note, this may have been the first straightahead jazz album I ever bought, on cassette no less. I must have worn that tape out, my neophyte ears perhaps befuddled by the improvisations but enjoying the spirit of the music nonetheless. Also, Sonny’s tenor saxophone seemed to embody the gritty yet sophisticated sound of classic jazz as I’d heard in sporadic previous experiences. Anyway, after finally acquiring the remastered CD many years later, I liked it even more. This session’s claim to fame is having Thelonious Monk sit in for two of his tunes, “Misterioso” and “Reflections”. While it is fun to hear Rollins and Monk reunited, the rest of the album satisfies just as much, with J.J. Johnson on trombone and the rhythm trio of Horace Silver, Paul Chambers, and Art Blakey. “Why Don’t I” and “Wail March”, both Rollins originals, kick things off with a zeal that, given the presence of Blakey and Silver, resembles what one might hear on a Jazz Messengers record. In the solos, Sonny surrounds melodic phrases with plenty of furtive runs, and Johnson, especially on “Wail March”, displays an agility not normally expected from his instrument. Next up are the Monk tunes, and Silver actually shares the piano bench with Monk in “Misterioso”. This deceptively elementary blues seems a little off kilter right from the first beat, but it develops into a showcase for the contrasting musical personalities involved. “Reflections”, taken at a medium gait, rises and falls in its compositional brilliance with Sonny’s tasty embellishments on top. The monkless quintet plays the two final numbers, of which “You Stepped Out of a Dream” is an assertive bop jam and “Poor Butterfly” brings some softness at last. (Funny how Silver employs a particular whole-tone fragment in his “Butterfly” solo, maybe as a nod to Monk?) There may be a few rough edges on this album, but everyone’s playing is quite energetic and emotionally on target.

Rather than the generic title given, I would have called this LP Reflections, or even Why Don’t Butterflies March Out of a Misterious Dream. Where’s Volume 1? Well, that’s a session from a year earlier that I’ve never owned, although it too is available in the Blue Note RVG series. But I can easily vouch for the performances on Volume 2.

The weird rhythmic conjunctions of “Asiatic Raes” and an ace “Tune Up” are among the highlights of this solid quartet album with Wynton Kelly, Doug Watkins, and Philly Joe Jones. All six tracks are good, especially the tenor-drums duet on “Surrey With the Fringe on Top”, which Rollins and Jones fill out so well that I was halfway through my first listen before realizing that bass and piano were absent. There’s something so satisfying about Rollins’ extended improvisations, even more so than Coltrane or Coleman could achieve in their zones. Sonny finds so many things within the usual parameters that no one else would ever think to say, and his spontaneous sense of structure is unbeatable. The leadoff “Tune Up” is the best version of this standby I’ve yet heard, thanks not only to Jones’ swing and Sonny’s exciting solo, but also Kelly’s piano solo. “Wonderful! Wonderful!” describes itself with very friendly, almost vocal tenor playing. “Blues for Philly Joe” is sort of a throwaway with entertaining work from Rollins and Jones. Kenny Dorham’s “Asiatic Raes” presents a formal challenge to which the quartet responds ably, and just try to keep that elastic melody out of your head.

The only thing to differentiate this Blue Note from Rollins’ preceding Prestiges is the slightly crisper sound. Anything else I could come up with would just be imaginary, even if I were to hint that the album feels more hurriedly dispatched than the classic Prestige sessions. The high quality of Newk’s improvising remains the same.

Rudy’s 2CD remaster hitches the original volumes 1 and 2 together and beefs up the thin sound as best it can. After leading a quintet and then a quartet for a stint at the Vanguard, Rollins had reduced the personnel by the time of this recording to a trio. Donald Bailey and Pete LaRoca back Rollins for an early portion and Wilbur Ware and Elvin Jones take over the bass and drums from there. This isn’t the Elvin we would come to know with Coltrane, yet his drumming concept is looser than the strict cadences of a Max or Philly Joe. Ware is a strong supporting bassist, and together he and Jones provide more than enough impetus to Rollins. Material ranges from a couple of Cole Porters to modern jazz tunes (Gillespie) to various standards to a sassy original blues (“Sonnymoon for Two”). As with the preceding albums, the tunes are gateways to Rollins’ in-depth improvisations, all the deeper due to the lack of piano and the freedom of a club performance. I prefer the Way Out West trio record for a few reasons, but I must admit that this live set is a meatier sample of Sonny’s ‘50s legacy, notwithstanding a few moments of water-treading. Rollins plays the Porter tunes as well as anyone, and he finds plenty of variations in the two takes of “Softly as in a Morning Sunrise”. His solo in “I’ll Remember April” sounds a lot like Ornette Coleman would on the Shape of Jazz to Come record a couple years later - singsong phrases in a piano-less vacuum. His relation to Elvin is key, and the drummer is to be credited for coaxing some things out of Sonny that he otherwise wouldn’t have played. At other times, we get the same riffing Rollins we heard on Saxophone Colossus, just in a rougher setting. The longer take of “Get Happy” is as fluid a statement as Rollins made in this era, and Ware and Jones get their spots as well.

These reels are always mentioned whenever people start waxing romantic about the historic albums taped at the Village Vanguard, and this also seems to be the Rollins title that so many successful modern musicians point to as an early influence and real-life textbook. I can understand that; listening to Sonny’s variations on common tunes, it’s a treasure chest of inspiration. Best to hear it in discrete chunks, where the value of the playing can be fully digested.

Rehearing the 2008 ‘Keepnews Collection’ remaster (which still sounds a little worn, alas), I’m reminded of some of the interesting turns the lengthy title track takes. Rollins titled “The Freedom Suite” for social concerns, though the name also references the open-ended trio format (Oscar Pettiford on bass, Max Roach on drums) and perhaps the LP-length freedom of a 19-minute track. The first several minutes explore a simple, happy melody, capped by a drum solo, then the trio goes into a merry-go-round 6/8 interlude with a neat bassline. A minute later, a yearning ballad line enters, over which Rollins solos in the genial manner of Way Out West. (Oscar gets a solo, too.) Then the waltzing interlude returns, followed by a final uptempo section, dashed with a refreshing dose of bop energy. Many listeners rank “The Freedom Suite” among Rollins’ best works, and while I tend to agree, I do think a piano would have improved certain parts, and barring the final minutes, it doesn’t have a very continuous impact. The second half of the album delves into a series of pat standards, including a waltz in “Someday I’ll Find You” and the syrupy “Till There Was You”, of which two alternate takes are present. I think Sonny solos best in “Will You Still Be Mine” - listen to that delicious line from 1:00 to 1:07. Also in the bonus cache is a Pettiford-Roach duet on “There Will Never Be Another You”, recorded while they were waiting for the leader to arrive. Both men play spiffily, particularly Max on the brushed breaks, but this track inevitably wears a vacancy sign.

I consider The Freedom Suite pretty good on its own terms and a worthy trio recording to sit alongside Way Out West and the Village Vanguard set. But to my ears, The Freedom Suite is less fulsome than either of those other titles, its structural uniqueness notwithstanding.

A six-disc package. Rollins emerged from a couple years’ sabbatical with a gnarled, rawer tone and a new phrasebook that ran to the dour and sardonic, replacing his good cheer of the decade before. This isn’t to say he became ugly, only different and more tonally expressive. The first fruit to blossom was the quartet date The Bridge, featuring guitarist Jim Hall in the foil role. And what a great blend they are: the tenor airs sharp new slogans counterpointed by calm and quick-witted guitar. “Without a Song”, “John S”, and the title track each strip standard bop down to an edgy modernity, while the ballads (including “God Bless the Child”) cut like knives. If you can only take home one of the RCA Victors, The Bridge is the prime choice, one of the best records of its decade. The second don’t-miss outing in this box is Sonny Meets Hawk, where Rollins hosts idol Coleman Hawkins and the two do everything except turn it into a lovefest. For one thing, it’s obvious that Hawkins isn’t here to stand for the old guard. You probably can’t find a more liberated performance from him. Sonny, meanwhile, is vicious with his playing, going even further afield than his elder, sometimes mocking Hawk’s lines, sometimes mocking the conventions of saxophone, period. This is the Real Tenor Madness, as the two bypass cliches and wind up with some unique music. Pianist Paul Bley furthers the offbeat atmosphere whenever he’s allowed to pull his chair up to the table. The only thing marring the album is the distortion of some of the tape, and I don’t know if the individual remaster fixed this. The third session that must be heard is the rendezvous with Don Cherry, Bob Cranshaw, and Billy Higgins, i.e., Sonny Meets Ornette (By Proxy), just as Coltrane did with far less amazing results. On the lengthy live tracks “Oleo”, “Dearly Beloved”, and “Doxy”, Higgins’ beats and Cherry’s trumpet nudge Rollins into new territory. There are many small pleasures, like the way Sonny deconstructs the theme of “Doxy”, and Cranshaw’s deft solo in same, the suite-like form of “Dearly Beloved”, and the sudden blues tangent in “Oleo”. Sonny spends some of his solo time simply phrasing against the drums, getting used to Billy’s accents, and once oriented, he takes off into squirrelly routes. Though awkward at times, there are moments where the players all fit together. One thing worth noting is that this is the most team-oriented playing you’ll hear from Rollins, as he and Cherry exchange phrases with eerie telepathy. Later, the band went into the studio with Henry Grimes on bass and cut three rewired standards, each short and eccentric. The other half of the collection is a mixed bag. The What’s New bossa session boasts a lush “Night Has a Thousand Eyes” with Jim Hall and a stark tenor/conga duet called “Jungoso”, both great tracks. On the other hand, “Don’t Stop the Carnival” and “Brown Skin Girl” are visited by an awful, anonymous vocal squad that sounds like floating skulls from hell, drunk on the underworld’s cheapest sangria. The Now’s The Time and Standard Sonny Rollins dates address classic jazz and show tunes with scattershot results. Cameos by Hall, Hancock, and Thad Jones don’t displace Rollins from center focus, where the tenor is at his most erratic. “St. Thomas” sits in the shadow of the original, while “Django” and “Travelin’ Light” make much use of Sonny’s newfound sonorities. “Four” is given three workouts, all of them with amazing solos. The tracks range from three-minute skimmers to obsessive, quarter-hour blowouts like “Now’s the Time” and “52nd Street Theme”. Those two have the single-minded intensity of Coltrane’s playing; both are alternate takes gone awry, but no one was going to yell “cut” when Sonny was on his quest. Inspiration comes and goes, as does sincerity. Is Rollins paying homage or being sarcastic with some of these tunes? Hard to say.

To sum up the box, there are three great sessions, each different from the other, and three hit or miss sessions with some very high points. Coltrane and Coleman impacted Rollins’ thinking in this period, though Sonny could never erase his incredible self-legacy. He took some time off, regrouped, and came back with an expanded conception. This collection views the new branches on the tree. If you’re already a Rollins fan, go for it. If you’re relatively new to the man, buy The Bridge and go from there.

I’m usually not a “best of” kind of jazz collector, but this 2006 sampler of Sonny’s three Impulse albums does the job well. It finds Rollins in his mid-60s raw-expression phase, emphasizing tenor sax timbres as much as purely musical ideas, as the first three tracks (from Sonny Rollins on Impulse) demonstrate. The melodic outpouring in “Three Little Words”, from the opening chorus to the solo cadenza, is classic uber-bop Rollins, while his wiry, reductive approach to “On Green Dolphin Street” scales a different sort of height. “Hold ‘Em Joe” returns to the catchy calypso style of “St. Thomas”, although it’s not as endearing. The rhythm trio of Ray Bryant, Walter Booker, and Mickey Roker provide the rhythm foundation on these three tracks. Rollins is an even finer surgeon in three selections from Alfie, an album of music he wrote for the film of the same name. He takes a lengthy and quite interesting solo over the optimistic “Alfie’s Theme” and sounds lovely in the light waltz “On Impulse”. The compositions grab as much attention as the sax playing – like the episodic “Street Runner with Child” – and excellent side contributions come from guitarist Kenny Burrell and pianist Roger Kellaway. Phil Woods and J.J. Johnson are part of the horn section arranged by Oliver Nelson. Wonderful music, and I mark “Alfie’s Theme” as one of Rollins’ best workouts ever. The two final tracks come from East Broadway Run Down (recorded in May 1966), Rollins’ boldest bid for free-jazz street cred, not counting the tryst with Don Cherry a few years earlier. Bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Elvin Jones bring a Coltrane connection, although Rollins plays absolutely nothing like Trane. In fact, he sounds at a loss for what to do in the 20-minute “East Broadway Run Down”, a half-baked foray despite trumpeter Freddie Hubbard’s presence and the rhythm duo’s cachet. Rollins honks single notes for a while, explores truncated tangents, and ultimately winds up blowing high-pitch bird noises from his mouthpiece. More satisfying is the showtune “We Kiss in a Shadow”, where Rollins spins luxurious phrases over the hypnotic Elvoid sway. The one track left out from EBRD is “Blessing in Disguise”, a thematic exploration that would have been a better choice than the title track, in my opinion.

Anyway, six of the eight cuts are top drawer, and the other two have certain merits, so Sonny’s Impulse Story is a valuable pickup for anyone new to this part of his catalog.

I’m not averse to Rollins’ later periods; I enjoy the two-disc Silver City compilation of Milestone work from the 1970s through the 1990s, along with the Sonny Rollins Plus 3 album of 1996, and I recommend those titles to any Sonny fans that haven’t heard them. But this collection of archival live recordings is almost a bust for me. The best thing I can say about Rollins’ later playing is that his breath is remarkably strong, but I don’t care if he blows 25 or 30 choruses when most of them feature the same drawn-out notes with curly vibrato. Somewhere along the way, he became almost like a “soulful” Saturday Night Live saxophonist with all the sexy wailing and whatnot. Maybe that’s a little harsh; Sonny is certainly someone to hear in person, but for home listening, I don’t think his later years are any advancement from his hardbop past. Gary Giddins, in the liner essay, notes the late 1970s as the beginning of Rollins’ peak period, with which I respectfully disagree. Any track from Saxophone Colossus or Newk’s Time blows this disc away with more melodic inventions, swing, and focused energy.

Road Shows Vol. 1 collects some supposedly primo live gems from the later eras recorded with various bands. Apart from “More Than You Know” and “Tenor Madness”, most of the tunes are lame, and the tenor solos contain more powerfully held notes and rhythmic jabs than melodic complexity. Rollins makes a great statement in “More Than You Know” (and there’s a good guitar solo, too), but I find him boring in, say, “Easy Living”, playing against a languid backdrop with an out of tune piano and ending with a cheap cadenza. Or the calypso “Nice Lady”, or the happy-sappy “Best Wishes”, where Sonny solos for a long time but doesn’t say much. The original “Blossom” is pretty nice, but again, I feel patronized by the solo. “Tenor Madness” has a few welcome jagged edges, although Sonny sounds sarcastic in tackling this classic blues. Please understand that these comments are relative to my preference for Rollins’ past works, as I consider him a jazz majesty no matter what, and it’s amazing that he’s still out playing passionately at an age when most people retire to the veranda. Nonetheless, Road Shows leaves me wanting the bop-based Rollins of old. Those who prefer his golden years might dig it.

|